Hello, happy Tuesday, and pardon my week’s hiatus. I’m back with, as promised, a bit more negativity than last week. I don’t want you guys to come to expect good vibes all the time! I also love to brood.

I was fortunate to spend the last two weeks in Laos, a place so spectacular I could gush about it in every essay I write this year. But I’ll spare you, and just say that I’ll never underestimate the majesty of rivers again; the Mekong is as marvelous as it is long, and taking lazy swims in it was a treat I’ll treasure forever.

Laos is a place, like much of Southeast Asia, that is only semi-recently developed for tourism (actually, Laos only began welcoming international visitors in 1989). Therefore, there’s a pretty set itinerary that many follow when they travel there, ourselves included. Like most, we went to Luang Prabang long enough to do the recommended hike and waterfall, then to Vang Vieng for the backpacker infamous “tipsy tubing,” then the Thakhek Loop, one of two bike loops travelers usually decide between.

Because of this sort of “standard route,” traveling in Laos means you’re constantly thrown in with other travelers. We’re all following the handful of English language blogs recommending hotels and restaurants, and we are all familiar with the places one another might be coming from or going to. There’s also a financial element—most travelers (or “backpackers”) come to Southeast Asia because of the comparable affordability, and therefore we all end up in the kind of “cheap but cute” hostel that is designed for our purposes. There, we drink Laos Beer and talk to each other, or sit alone and write in our journals while staring off into the distance.

Being a part of this backpacker cinematic universe on a trip like this always provides an interesting opportunity for me to hold up a mirror to myself. My internal monologue bounces chaotically between being judgmental of something they say or do, feeling mightier than thou, and then feeling ashamedly hypocritical and nasty for said judgment. After all, I too have a big backpack (*gasp*). Women contain multitudes. All the mental cartwheels feel like one of those bouncing “DVD” logos on an old TV set. It very rarely hits the perfect spot in the corner.

When I find myself chatting away with another twenty-something traveler, say at one of those hostels or in a company van to some prescheduled activity, there is by nature a lot of standard talking points: where we’ve been, where we’re going, what to eat, and how was the weather. This might then turn into favorite places, best foods, and best weather.

And this kind of travel recap conversation can sometimes lead to a point of commentary that has come, over time, to particularly stick with me. A girl I was seated next to on a bus last week, perfectly nice otherwise, said it very succinctly:

“The people in Laos just aren’t that nice.”

Other versions of this statement I’ve heard over the years include: “The people in Thailand were much nicer,” “Vietnamese people are a bit rude compared to here,” and “Cambodian people are way more happy and welcoming.” Etc, etc, etc.

It’s a sentiment that’s come to grind at me, and on this trip I came to realize how much it lingers in my head, and I began to wonder at the reason. It makes me feel the immediate need to change the subject, like we’re encroaching on a type of appraisal that I want no part of. And why? If so much about travel and backpacker culture has the capacity to be problematic, why is this one type of stantement irking me the most? I had many long transit rides in Laos to chew on it. And so I did, and now it becomes a blog post.

First: I’m going to be dramatically mean, just to get some of the worst thoughts off the top of my head so we can move on more cordially.

But like… what do all of these post-grads expect when they walk out of the airport door in Vientiane (or, insert other city here)? That a beautifully wrinkled local grandmother is going to greet them with a wide smile, a kiss on the cheek, and a flower in their hair? And then invite them to her home for a meal, maybe shots of local whiskey, just because the joy of our arrival is too great not to be basked in? Is it not enough to be allowed to explore a beautiful place and a one-dollar meal without also being doted upon by the person who serves it to you? Would you be giddy if you were trying to do your job and someone in 200-dollar hiking boots was bickering over the spare change of a taxi ride?

Okay, PHEW! Sorry about that! And now, a more genial contemplation.

I feel that as the baseline, this kind of statement (bemoaning the un-niceness of locals) puts into stark relief the troubling nature of travel as a whole: it’s sort of an inherently selfish act. Taking a trip is a means of self-gratification, whether that be just to have fun and unwind, or to achieve some sort of personal discovery. Now, I don’t necessarily think that’s evil. Having fun is a fantastic part of the human experience. And I buy into the idea that investing in oneself in any fashion can make us better people, and have consequences that are ultimately positive for more than just ourselves. But nonetheless, I find traveling is hard to untangle from “taking” and “extracting.” We’re often appreciating, of course, but very rarely adding to a place while we’re in it.

And this idea of ranking the people of a place based on their kindness to us sort of implies that we want to extract from them as well. We want the smiles, the good nature of the people we encounter, to add to our experience and to fit with the picture we held in our mind while we were planning the trip. In that picture, we were not only completely welcome, but beloved as well. Our arrival was not only invited but eagerly anticipated.

I also suspect that we as travelers crave a clean narrative from our adventures. We still want escapades, and maybe even safe mishaps or sticky situations that create an entertaining yarn later. But we don’t want an especially fraught story, especially one that implicates us negatively or that calls into question the virtue of our presence. We don’t know how to talk about the souvenir saleswoman who gave us a hard time for trying to haggle over price, because it calls to mind the possibility that our being in this place isn’t entirely positive. It’s an ugly thought. A friendly wave is far more palatable.

Another thing about these hopeful sparkling travel narratives is that they put the traveler at the center of the story, with the people they encounter as adornment. Local people are often seen as potential conduits for the “genuine” or “authentic” travel experiences that visitors badly want. I’ve known this first hand.

When I traveled in Vietnam for the first time during college, I felt the most alive, the most fortunate for the trip, in those rare moments when I was let into a card game at a homestay, or found myself tipsy off of rice wine I wouldn’t have known how to order by myself. Getting that inch closer to the culture is an immense joy when it’s bestowed, but that doesn’t mean it’s a gesture we are owed. And it doesn’t mean we should generalize people as less “nice” for not going out of their way to offer it.

If there is one easy, unselfish thing we can “give” as tourists, maybe it’s the space, the nonjudgment, to let the people we encounter exist as their own entities, capable of a wide breadth of experiences and emotions and not just as a means to brighten our own days or forward our own agendas. Not to be completely lame, but perhaps it would be worthwhile to assess our own niceness first before seeking it with little grounds for our deserving it.

And then, there’s money.

The reason so many young backpackers are found in Southeast Asia is because of the relative affordability. This affordability comes down to a variety of factors that I don’t fully understand and therefore can’t explain, but I know that a major reason is the relatively low cost of labor in these countries. In other words, people are paid less, and are “poorer” than, say, an average employee in the United States. And in the “west” (to make a sweeping generalization), we are kind of obsessed with the portrait of poor people as also the “happiest.” Something that could (and probably is) an entireessay topic in itself.

Sometimes I wonder if those of us with enough privilege to travel internationally want that to be true more than anyone else. As we hike through rice paddies, we want the reassurance that the woman over there, hauling a massive sack of soil, is, in fact, perfectly content.

Now, it’s not my place to say if she is or isn’t. Sure, I hardly know the woman. But I know my own day would be better (my hike less intruded by uncomfortable thoughts) were I guaranteed that she is, indeed, happy. And I can get that reassurance if she’s nice to me. If she returns my smile from across the field.

And is there a part of me that would be wounded if she didn’t? Or the tuk-tuk driver, the barista, the hotel staff. And perhaps later, over hostel beers, casually comment that people in so-and-so country weren’t as nice as I expected.

Finally, I just find it all hilariously silly in general, this insistence on labeling people “nice” or “not nice” while on a trip. Because regradless of the attitude is the fact that in Laos, like so many places, I personally would have been completely useless, lost, helpless, etc without the local people.

I try hard to be a good planner, and still, like my fellow backpackers, I am just a little baby who needs their hand held by Dad (Dad being whatever bus driver or tourism agent finds themself in charge of me in that moment).

Take, for instance, when Phoebe and I were going from Don Det, an island in the far south of the country, to Vientiane, the capital city 500 miles north. We booked a three-part ticket (boat, van, sleeper bus), but we didn’t fully understand how each leg of the journey would work. When we got off the ferry boat and found ourselves on a random beach with no ticket counter in sight, there was nothing to do but wander around and hope that someone would help us.

Eventually, a van driver (who had evidently been told to look out for two pathetic girls) called to us from the road, and we were off. Affable or not, completely helpful, and the only way we’d have been able to get where we needed to be.

Now, this was probably all a bit “much.” I sort of feel like Kate Hudson at the beginning of “How to Lose a Guy in 10 Dates,” trying to write about peace in Uzbekistan for Composure fashion magazine. Yes, in this metaphor, Kitchen Sink is equivalent to a fictional national fashion magazine.

And I hope I didn’t give the impression that I think it’s vile to observe and appreciate the kindness of others when on a trip. It’s breathtaking how kind the world can be, especially as someone hailing from a country that is becoming more and more miserly with its generosity by the day. Nor do I hope to make all travelers out to be misguided; they often possess a curiosity and love for the world that I find challenging to match.

It’s all simply to say that I, personally, am coming to check myself a bit when it comes to lamenting a lack of outward “niceness” from those in places I’m simply passing through. And to remember not to expect friendliness, but to treat it with the appreciation it deserves when I recieve it.

And for what it’s worth, I’ve never been anywhere that lacks lovely people.

Do you have any thoughts/ opinions/ differing ideas/ two cents on this topic? Leave a lil’ comment! I want to hear.

The bullet points:

Last week, I published my first paid piece in a major magazine. It was just a silly listicle about snakes, but I was (am) nonetheless giddy to have written for Smithsonian.

This weekend is Ellie’s birthday, which means Harry Potter party!

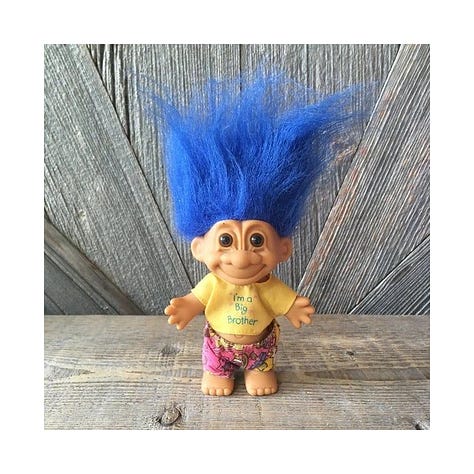

I dyed the bottom half of my hair blue (which is actually perfectly in theme with this liberal rant), and here are some things I look like now:

Love,

Ryley

If you’re enjoying Kitchen Sink and are interested in supporting my work, you can always Buy Me a Coffee.

Loved it! Great approach to travelling. I've lived in Laos for 18 years and worked in destination marketing. Surveys show Laos' USP is its hospitable people and relaxing atmosphere. This tourist may have had wildly high expectations. Lao people may be poor and happy. Better than being poor or wealthy and unhappy

Great post Ryley! I find that living in a place that is often filled (to the brim) with tourists, it can be challenging not to grumble. And I often have to remind myself that they are providing a financial benefit to a large number of people in our community. Annnd, I am not hauling a large bag of dirt around in order to feed my family! But…I still have many days where I am not returning smiles . 😉